The grim reality

Great news – we were granted HIF seed-funding to get our project off the ground! Next our team of experts in communication disability, research, SGBV, humanitarian response and innovation needed to understand each other’s field in more depth to work together effectively. We started to look at the literature on communication disability, forced displacement and SGBV.

As we expected, there is a lot of research and evidence on the vulnerability of people in forced displacement – particularly women and girls – to SGBV. The breakdown of communities, loss of family ties, cramped conditions and reduced privacy and possible risky behaviours (such as collecting firewood alone) increase their vulnerability as targets of abuse. Humanitarian agencies recognize this huge risk and UNHCR and its partners have SGBV response and support programmes in place , but there are still enormous barriers preventing survivors of SGBV from reporting abuse and accessing support.

A ‘culture of silence’ is commonplace due to stigmatization, and feelings of guilt and shame deter survivors from reporting. It is even more difficult if the perpetrator is a close friend or family member, and people with disabilities are more vulnerable to intimate partner violence.

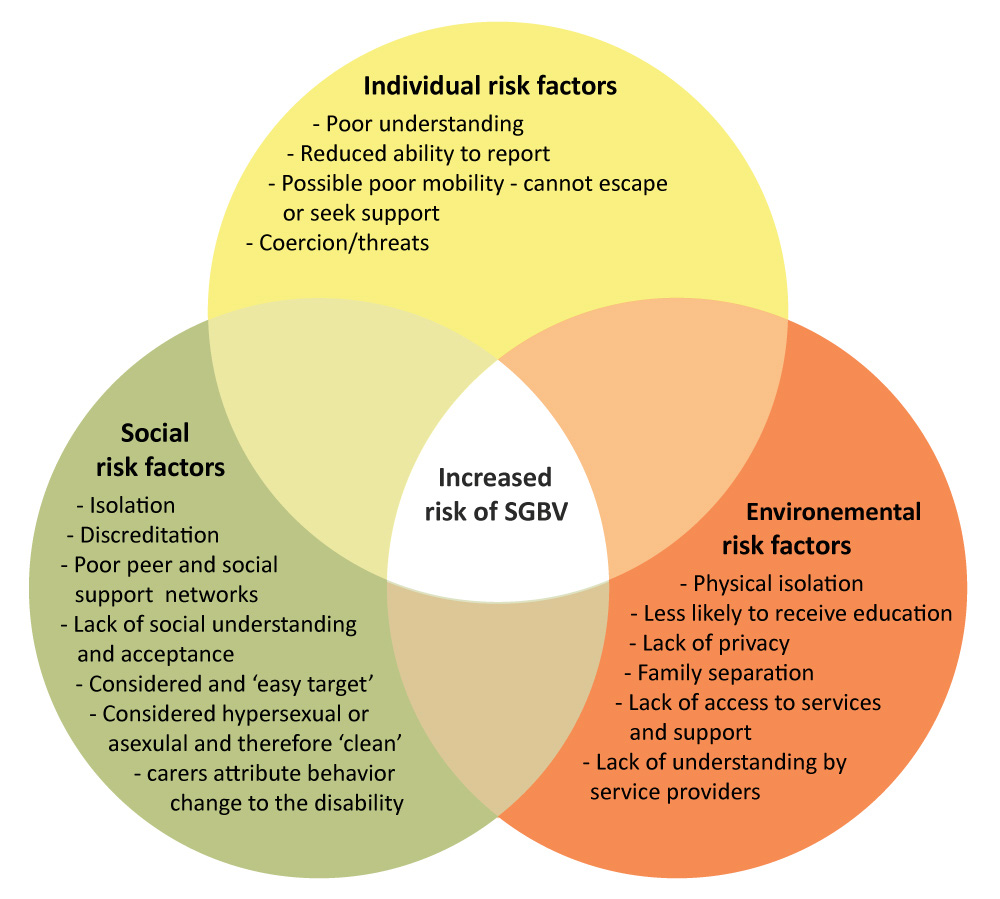

What if you have a disability? A great deal of evidence exposes the increased risk to SGBV of people with disabilities across the globe, most acutely in forced displacement. Prevention and response programmes often fail to cater for the specific needs of people with disabilities on all levels and, even when a person with a disability does report an instance of abuse, they are often not taken seriously by friends, family or support services. The risk factors are acknowledged to be individual, environmental and social (see diagram). The most vulnerable to SGBV are those (often children) with intellectual impairments. Why? Because their understanding of what has happened is reduced, their support networks are limited and they are UNABLE TO REPORT ACCURATELY!

Communication disability (when a person’s ability to understand and / or use spoken language) can occur on its own or as part of a wider condition. People with hearing impairment, intellectual impairment, developmental disabilities or acquired conditions (such as from head injury or stroke) can have difficulties understanding what others say to them and expressing themselves. Described by perpetrators as ‘the perfect target’ due to their reduced ability to report abuse, people with communication disability are some of the most vulnerable to SGBV. Up to 49% of people with disabilities are estimated to have some form of communication difficulty and some evidence suggests that up to 75% of non-verbal people have experienced abuse – often long-term and in multiple forms.

For people with communication disability in forced displacement contexts, the risk of SGBV is a grim reality. Services for people with communication disability in resource-limited countries are either absent or in extremely short supply. Front-line staff are aware of the difficulties people with communication disability face across the SGBV response systems but are ill-equipped to respond. Some humanitarian organizations have used sign interpreters for people with hearing impairment, only to find that most people either do not use the sign language of their host country, or do not sign at all as they have not been to a school for the deaf. Some have used photographs or other visual materials to help people to communicate some basic information but are unsure how to proceed with any identified cases of abuse. Police and legal services tend not to take any reports forward to prosecution as statements are deemed unreliable. Only clear medical signs of abuse can be taken in evidence. Survivors cannot access counselling based on talking therapy. Perpetrators walk free.

There is very little research on SGBV in forced displacement that involves people with communication disabilities as participants and still less that includesd people with communication disabilities as co – researchers andinformers and/ or as service planners. Humanitarian organizations confess that they do not yet have the knowledge, skills or capacity to support their involvement. Though the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities is clear in stating that people with disabilities should be included in the design and implementation of services, people with communication disabilities continue to fail to realize their right to protection from SGBV.

The literature review confirmed the concerns highlighted in a UNHCR Rwanda 2015 mission report on the vulnerability of people with communication disabilities to SGBV in refugee communities in Rwanda. The next steps? To find out the nature and scale of the problem in Rwanda, to raise awareness of the vulnerability of people with communication disability, to SGBV amongst key stakeholders and service providers and to bring a consortium of expert organizations together who can support refugee-survivors of SGBV with communication disability in their programming, ensuring no one is left behind.

Helen Barrett: www.communicabilityglobal.com @communiglobal

Julie Marshall: www.mmu.ac.uk @jemarshall13

Sidra Anwar: www.unhcr.org @RefugeesRwanda

Lise Capet: www.humancentreddesign.org @IHCDDesign

Stay updated

Sign up for our newsletter to receive regular updates on resources, news, and insights like this. Don’t miss out on important information that can help you stay informed and engaged.

Related articles

.png)

Explore Elrha

Learn more about our mission, the organisations we support, and the resources we provide to drive research and innovation in humanitarian response.