A quality improvement approach to ameliorate reproductive health services in an emergency context in the DRC

The Second Congo War in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) officially ended in 2003. Yet even more women are dying from complications of pregnancy and childbirth now than they were during the war. New survey results reveal maternal mortality in the DRC was higher during 2007-2014 than it was during 2003-2007, despite the country enduring war from 1996-2003.

Why is this happening, and what can it tell us about women’s health in areas of conflict? While the hostilities ended in 2003, ongoing insurgency violence from dozens of national and international rebel groups has continued through to today. Traditionally war can cause increased maternal mortality due to social and economic disturbances, including “disruption of health services, poor food security, deterioration of infrastructure and population displacement.” However, the DRC is still facing these issues in a time not formally characterised as one of war. The short and medium term effects of conflict on population health are reasonably well documented. Less considered are its consequences across generations, and the potential harms to the health of children yet to be born.

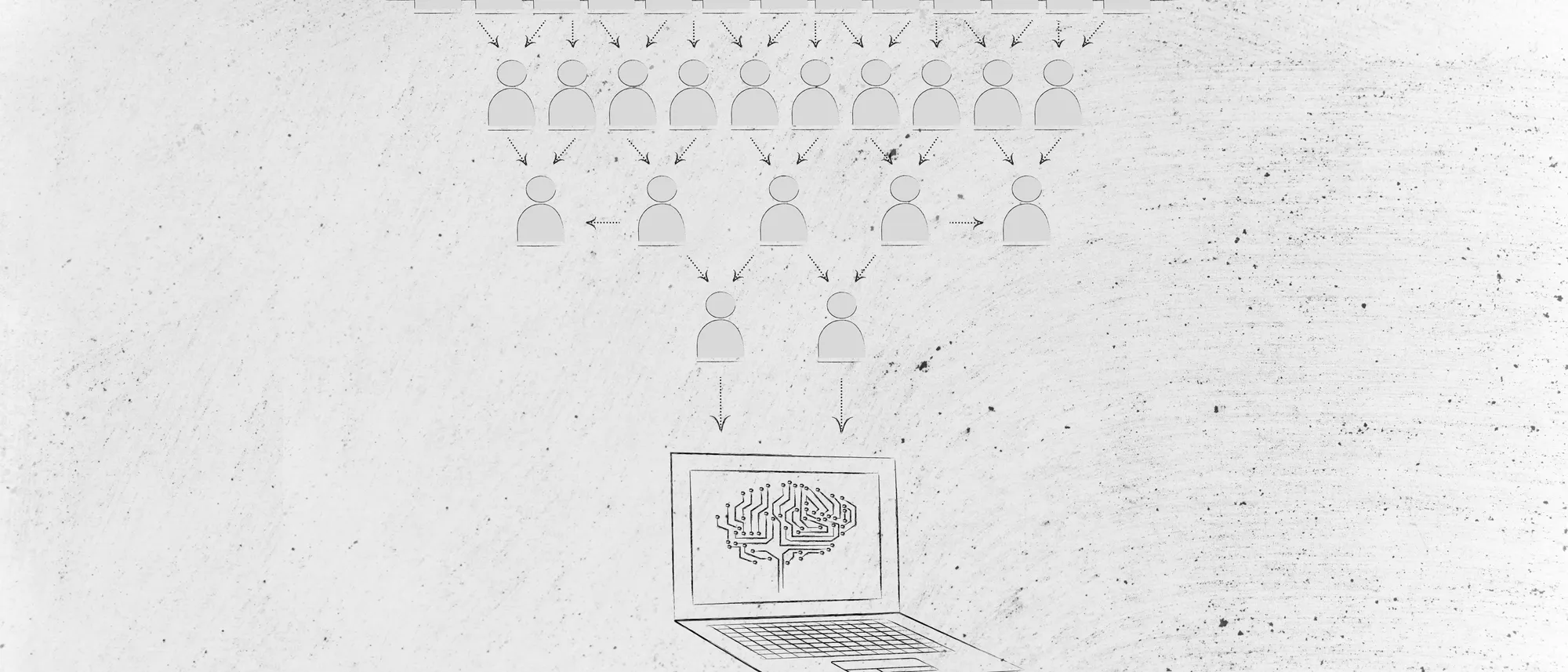

The International Medical Corps along with its partners the Centre for Disease Control (CDC), the University Research Co., LLC (URC) and the UNFPA have, for a year, been carrying out research amongst affected populations in order to better inform effective improvement in reproductive health care services to IDPs.

Chambucha and Hombo Nord are two communities within the Itebero Territory that benefited from the project. These communities have a population estimated at about 26,059 people, many of whom have been the victims of looting, rape and sexual violence - many displaced several times in a region which has also hosted IDPs fleeing clashes between armed groups. No state services exist in these localities, not even law enforcement. In these localities, it is elements of Raiya Motomboki - an armed group - who dictate the law.The Second Congo War in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) officially ended in 2003. Yet even more women are dying from complications of pregnancy and childbirth now than they were during the war. New survey results reveal maternal mortality in the DRC was higher during 2007-2014 than it was during 2003-2007, despite the country enduring war from 1996-2003.

Why is this happening, and what can it tell us about women’s health in areas of conflict? While the hostilities ended in 2003, ongoing insurgency violence from dozens of national and international rebel groups has continued through to today. Traditionally war can cause increased maternal mortality due to social and economic disturbances, including “disruption of health services, poor food security, deterioration of infrastructure and population displacement.” However, the DRC is still facing these issues in a time not formally characterised as one of war. The short and medium term effects of conflict on population health are reasonably well documented. Less considered are its consequences across generations, and the potential harms to the health of children yet to be born.

The International Medical Corps along with its partners the Centre for Disease Control (CDC), the University Research Co., LLC (URC) and the UNFPA have, for a year, been carrying out research amongst affected populations in order to better inform effective improvement in reproductive health care services to IDPs.

Chambucha and Hombo Nord are two communities within the Itebero Territory that benefited from the project. These communities have a population estimated at about 26,059 people, many of whom have been the victims of looting, rape and sexual violence - many displaced several times in a region which has also hosted IDPs fleeing clashes between armed groups. No state services exist in these localities, not even law enforcement. In these localities, it is elements of Raiya Motomboki - an armed group - who dictate the law.

The health centres of these communities benefited from the quality improvement component of the project and health personnel were trained to improve the quality of reproductive health services provided to their patients. After the training, regular coaching sessions are held by International Medical Corps to evaluate the activities of the staff who received the training to ensure they are implementing what they learned.

"My name is Mapenzi Isaya – I am 25 years old, a mother of 3 and a midwife at CS Hombo Nord. I am one of the beneficiaries of the training on Basic Emergency Obstetric and New-born Care (EmONC). Thanks to the training I received from International Medical Corps I now know how to identify and best treat cases of postpartum haemorrhage. We were also trained in essential care of new-born children, how to perform manual vacuum aspiration (MVA) and techniques around the active management of third stage labour (AMTSL).

During the training we were taught about the importance of the quality of our work. We were told that it is not only important to look at what we do, but how we do it. We have been receiving regular coaching sessions and meetings from the quality improvement team who help us to better understand and practice what we were taught. I am very happy because in our community, the cases of postpartum haemorrhage has decreased and I thank International Medical Corps for the work they have done. May God continue to bless them so that they can do more and also help other communities."

International Medical Corps continue to distribute drugs to all arms of the project and providing coaching to health staff of the arm for quality improvement.

Though there are many achievements of the project, we equally face many challenges in delivering this programme - some of which include the routes we must take to carry out the research and the effective deliveries of trainings that are difficult and dangerous. The project uses community health workers (CHWs) to carry drugs on their head to remote and inaccessible health facilities – the CHWs sometimes walking for up to 3 days to do this.

The second major challenge is that the Itebero health zone is highly insecure, with armed groups operating within the communities we are supporting, and at times there are cases of looting across the areas – sometimes targeting health facilities. The good thing is that International Medical Corps is completely neutral and we do not interfere in anything that could jeopardise our projects. This enables us to carry out our work in all communities undisturbed, as our reputation of neutrality is well known.

Stay updated

Sign up for our newsletter to receive regular updates on resources, news, and insights like this. Don’t miss out on important information that can help you stay informed and engaged.

Explore Elrha

Learn more about our mission, the organisations we support, and the resources we provide to drive research and innovation in humanitarian response.