Listening to Those Who Lived Through Ebola Trials First-hand

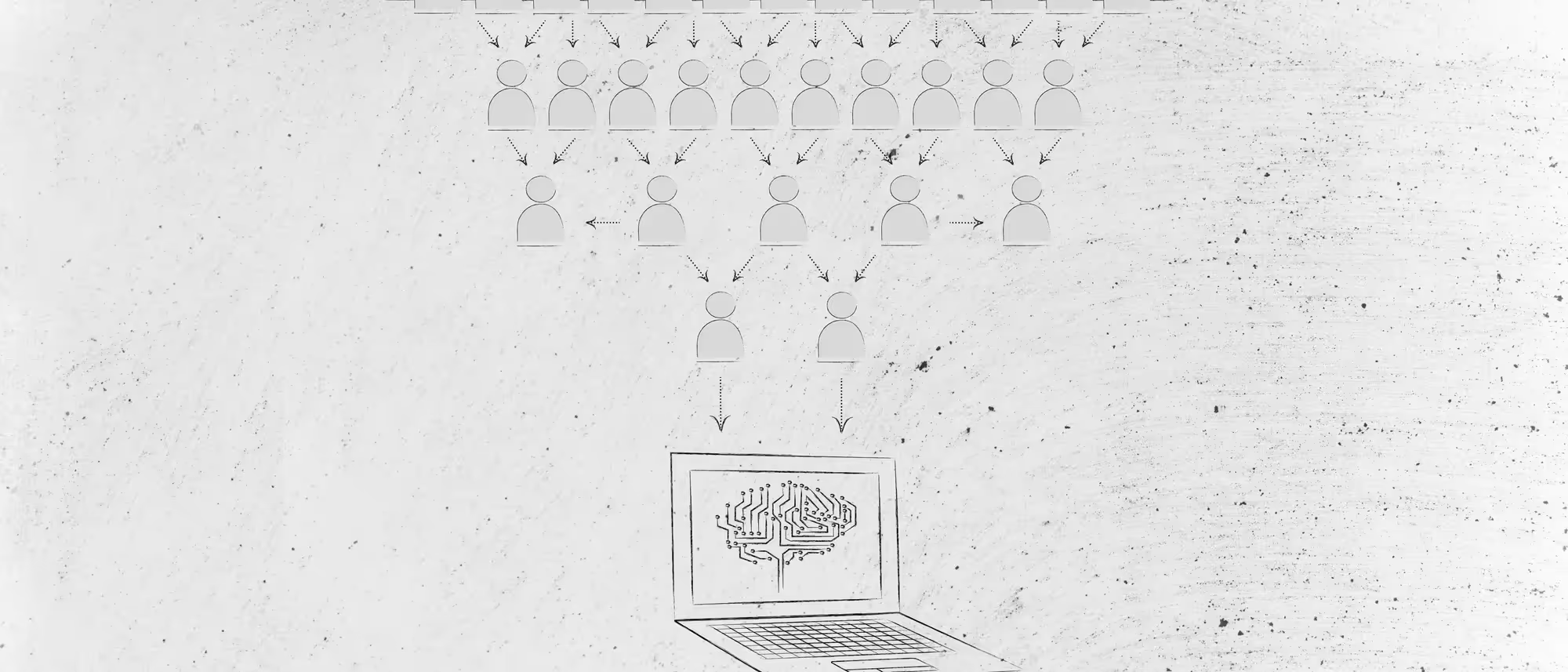

As part of a qualitative study, since December 2016 we have been gathering accounts of research conducted during the West Africa Ebola outbreak. Our focus is on stakeholders in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia: research team members, ethics committee members, trial participants and their families, as well as community leaders.

Our analysis is ongoing at this point, but a number of themes strike us as sufficiently clear to highlight at this point. These include the importance of post-trial communications, the challenges of informed consent in public health emergencies, and trans-national research collaboration priorities and concerns.

Importance of post-trial communications: Some of those interviewed expressed frustration as a result of limited or no follow-up to their participation in trials. The lack of follow up communications led some to doubt the safety of interventions, fear for their future health, or express feeling like ‘guinea pigs’. Several participants and researchers expressed that they may not collaborate in future with those researchers who let them down by failing to inform them of study results.

[caption id=attachment_9411" align="alignleft" width="300"]

Ebola public health mural outside Université de Sonfonia, Guinea[/caption]

Informed consent: Not all people who received medication, vaccines, or other interventions understood their experimental nature. Some interviewees who had participated in efficacy trials recalled being assured by clinicians that the experimental intervention would protect them from Ebola and save their lives. Such misunderstandings emerged regularly amongst those interviewed with low literacy.

Fair collaboration and capacity building:Power imbalances between different research-involved parties, exacerbated by the urgency of the situation, were reported to have stifled negotiations over control of research materials. A few local researchers working with international teams felt they were included as a matter of tokenism, rather than as equal partners.

Bio-sample ownership and stewardship:At the onset of the epidemic, the affected countries lacked clear processes for dealing with biosafety-level-4 bio-samples. Because facilities for storing and analyzing such samples were in most cases not available locally, samples collected during the epidemic were exported. The question raised by many was why, during the two years the epidemic persisted, could funds not be found to build adequate research facilities in West Africa? This was connected to frustrations over lost opportunities for capacity-building, as the existence of a proper storage facility locally might have ensured continued research opportunities for a new generation of local researchers.

Research priorities from the ground up

The WHO calls for research priorities to be set carefully during infectious disease outbreaks. Particularly in resource-scarce settings, WHO suggests that provisions for local capacity building should be anticipated and “research should not be done if it will excessively take away resources...from other critical clinical and public health efforts”1. WHO has also called for meaningful involvement of affected countries in a new international biobank2. Our preliminary research findings support these recommendations, and echo others emphasizing that Ebola research should prioritize respectful engagement with local actors, featuring careful consent processes and capacity building 3,4. The therapeutic misconception (confusion of research with treatment) in particular poses a major challenge in Ebola-affected countries and merits constant attention if consent is to be meaningful. We add to this the crucial role in trust-building of consistent and ongoing communication with local trial staff and participants even after trials end.

Authors: Elysée Nouvet, Lisa Schwartz, Ani Chenier, Nicola Gailits, John Pringle, Matthew Hunt, Carrie Bernard, Oumou Bah-Sow

Acknowledgements:

The commentary is based on an ongoing study “Perceptions and Moral Experiences of Research conducted during the West Africa Ebola outbreak” funded by R2HC-ELRHA (Grant #19852).

Ethics:

This study has received Ethics approval from the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board (Hamilton, Canada), the Comité National d’Ethique en Recherche de la Santé, the University of Liberia, and the Sierra Leone Ethics and Scientific Review Committee.

Conflicts of interest: We have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References:

1 World Health Organization. Guidance for Managing Ethical Issues in Infectious Disease Outbreaks. 2016.

2 Saxena, A., & Gomes, M. Ethical challenges to responding to the Ebola epidemic: the World Health Organization experience. Clinical Trials, 201613:96-100.

3 Osterholm, M., Moore, K., Ostrowsky, J., Kimball-Baker, K., Farrar, J., & Team, W. T. C. E. V. The Ebola Vaccine Team B: A Model for Promoting the Rapid Development of Medical Countermeasures for Emerging Infectious Disease Threats. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 201616:e1-e9.

4 Lane, H. C., Marston, H. D., & Fauci, A. S. Conducting Clinical Trials in Outbreak Settings: Points to Consider. Clinical Trials. 201613:92-95.As part of a qualitative study, since December 2016 we have been gathering accounts of research conducted during the West Africa Ebola outbreak. Our focus is on stakeholders in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia: research team members, ethics committee members, trial participants and their families, as well as community leaders.

Our analysis is ongoing at this point, but a number of themes strike us as sufficiently clear to highlight at this point. These include the importance of post-trial communications, the challenges of informed consent in public health emergencies, and trans-national research collaboration priorities and concerns.

Importance of post-trial communications: Some of those interviewed expressed frustration as a result of limited or no follow-up to their participation in trials. The lack of follow up communications led some to doubt the safety of interventions, fear for their future health, or express feeling like ‘guinea pigs’. Several participants and researchers expressed that they may not collaborate in future with those researchers who let them down by failing to inform them of study results.

[caption id="attachment_9411" align="alignleft" width="300"]

Ebola public health mural outside Université de Sonfonia, Guinea[/caption]

Informed consent: Not all people who received medication, vaccines, or other interventions understood their experimental nature. Some interviewees who had participated in efficacy trials recalled being assured by clinicians that the experimental intervention would protect them from Ebola and save their lives. Such misunderstandings emerged regularly amongst those interviewed with low literacy.

Fair collaboration and capacity building:Power imbalances between different research-involved parties, exacerbated by the urgency of the situation, were reported to have stifled negotiations over control of research materials. A few local researchers working with international teams felt they were included as a matter of tokenism, rather than as equal partners.

Bio-sample ownership and stewardship:At the onset of the epidemic, the affected countries lacked clear processes for dealing with biosafety-level-4 bio-samples. Because facilities for storing and analyzing such samples were in most cases not available locally, samples collected during the epidemic were exported. The question raised by many was why, during the two years the epidemic persisted, could funds not be found to build adequate research facilities in West Africa? This was connected to frustrations over lost opportunities for capacity-building, as the existence of a proper storage facility locally might have ensured continued research opportunities for a new generation of local researchers.

Research priorities from the ground up

The WHO calls for research priorities to be set carefully during infectious disease outbreaks. Particularly in resource-scarce settings, WHO suggests that provisions for local capacity building should be anticipated and “research should not be done if it will excessively take away resources...from other critical clinical and public health efforts”1. WHO has also called for meaningful involvement of affected countries in a new international biobank2. Our preliminary research findings support these recommendations, and echo others emphasizing that Ebola research should prioritize respectful engagement with local actors, featuring careful consent processes and capacity building 3,4. The therapeutic misconception (confusion of research with treatment) in particular poses a major challenge in Ebola-affected countries and merits constant attention if consent is to be meaningful. We add to this the crucial role in trust-building of consistent and ongoing communication with local trial staff and participants even after trials end.

Authors: Elysée Nouvet, Lisa Schwartz, Ani Chenier, Nicola Gailits, John Pringle, Matthew Hunt, Carrie Bernard, Oumou Bah-Sow

Acknowledgements:

The commentary is based on an ongoing study “Perceptions and Moral Experiences of Research conducted during the West Africa Ebola outbreak” funded by R2HC-ELRHA (Grant #19852).

Ethics:

This study has received Ethics approval from the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board (Hamilton, Canada), the Comité National d’Ethique en Recherche de la Santé, the University of Liberia, and the Sierra Leone Ethics and Scientific Review Committee.

Conflicts of interest: We have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References:

1 World Health Organization. Guidance for Managing Ethical Issues in Infectious Disease Outbreaks. 2016.

2 Saxena, A., & Gomes, M. Ethical challenges to responding to the Ebola epidemic: the World Health Organization experience. Clinical Trials, 201613:96-100.

3 Osterholm, M., Moore, K., Ostrowsky, J., Kimball-Baker, K., Farrar, J., & Team, W. T. C. E. V. The Ebola Vaccine Team B: A Model for Promoting the Rapid Development of Medical Countermeasures for Emerging Infectious Disease Threats. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 201616:e1-e9.

4 Lane, H. C., Marston, H. D., & Fauci, A. S. Conducting Clinical Trials in Outbreak Settings: Points to Consider. Clinical Trials. 201613:92-95.

Stay updated

Sign up for our newsletter to receive regular updates on resources, news, and insights like this. Don’t miss out on important information that can help you stay informed and engaged.

Explore Elrha

Learn more about our mission, the organisations we support, and the resources we provide to drive research and innovation in humanitarian response.