Applying the Model for Improvement to refugee and IDP settings

Democratic Republic of the Congo has suffered the impact of violence for two long decades, both within its borders and as a result of neighbouring conflicts. In December 2015, UNHCR estimated there were about 170,000 refugees residing in DRC that had fled conflict from Central African Republic (CAR), Rwanda, Burundi and other countries. According to OCHA, more than 7.5 million people are now in need of humanitarian assistance in the country. Many have been displaced due to violence in the east.

North Kivu has been the epicentre of war for the past two decades and remains the greatest challenge to stability in the country. Only about 6% of internally displaced people (IDPs) live in camps in North Kivu. The rest live within the communities, which means that both IDP and host communities are affected by the ongoing conflict. Armed groups have directly targeted civilians and used systematic sexual violence as a weapon, particularly against women and girls.

These issues have undermined progress in reproductive health prevention, and made it particularly difficult to deliver vital treatment programmes to those who need them the most.Democratic Republic of the Congo has suffered the impact of violence for two long decades, both within its borders and as a result of neighbouring conflicts. In December 2015, UNHCR estimated there were about 170,000 refugees residing in DRC that had fled conflict from Central African Republic (CAR), Rwanda, Burundi and other countries. According to OCHA, more than 7.5 million people are now in need of humanitarian assistance in the country. Many have been displaced due to violence in the east.

North Kivu has been the epicentre of war for the past two decades and remains the greatest challenge to stability in the country. Only about 6% of internally displaced people (IDPs) live in camps in North Kivu. The rest live within the communities, which means that both IDP and host communities are affected by the ongoing conflict. Armed groups have directly targeted civilians and used systematic sexual violence as a weapon, particularly against women and girls.

These issues have undermined progress in reproductive health prevention, and made it particularly difficult to deliver vital treatment programmes to those who need them the most.

Training to improve care

In order to effectively improve reproductive health care services for those forced to leave their own homes, two major components must be considered: what is being done (content) and how it is being done (process of care).

As I mentioned in the previous blog entry, the Minimum Initial Service Package (MISP) was established by the Inter Agency Working Group for Reproductive Health in Crises as a set of priority activities to be taken in a coordinated manner by trained staff during the onset of an emergency.

These priority areas make up the clinical content, representing best practice – built on experience and evidence - which when applied will improve care for every patient every time. The priority areas are aimed at coordination of the MISP, prevention and response to sexual violence, prevention of HIV transmission, prevention of increased maternal and newborn morbidity and mortality, and planning for comprehensive reproductive health services.

In order to prevent maternal and newborn morbidity and mortality, a competency based training on basic emergency obstetric and newborn care (EmONC) was conducted for health workers responsible for conducting deliveries.

Consistency of process

The second step is the process. The most significant improvement comes when critical content is combined with development in the organisation of care (processes) for consistent implementation in each local context. Process improvement addresses the barriers and bottlenecks that limit the implementation of the content through small changes to the process of care. For example, oxytocin needs to be available and maintained at the correct temperature at all times. Sometimes oxytocin is stored far from the maternity therefore preventing timely administration. This is one of the barriers that would be addressed in the process.

Working in refugee settings

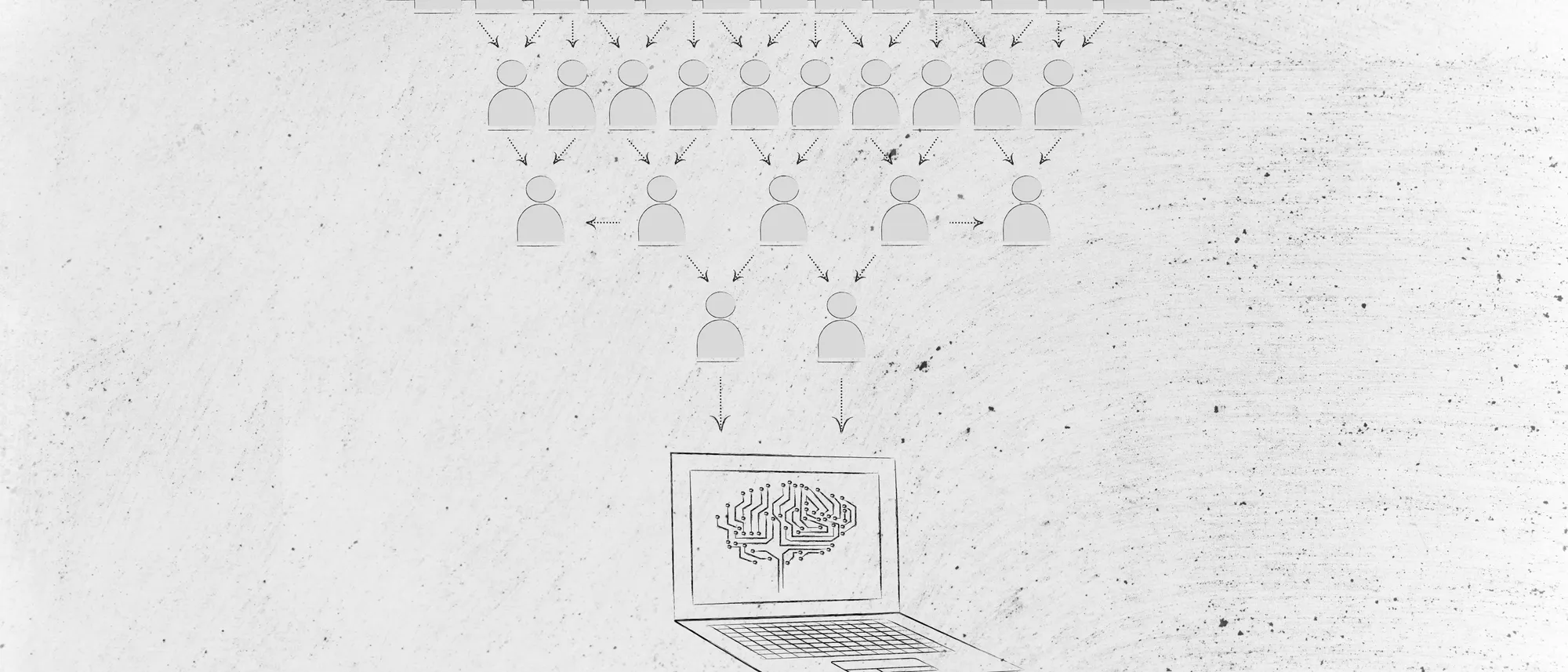

The Model for Improvement is an approach to testing change - based on three questions and the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle. The three questions are: (1) What are we trying to accomplish? (2) How will we know a change is an improvement? And (3) What changes can we make that will result in improvement?

The Model for Improvement has been successfully applied in a wide variety of health care and social service settings in low and middle income countries, contributing to improved care for maternal and child health, HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis. However, there has been no applications of this approach to the specific context of supporting refugees and IDPs. Given the evidence, it appears that introducing a quality improvement approach in facilities implementing the Minimum Initial Service Package (MISP) will improve the provider capacity, service delivery and the ability of local partners to provide high quality services in emergency and protracted conflict settings.

What have we achieved?

In the first phase of this project International Medical Corps conducted a baseline assessment with technical assistance from The Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, conducted competency-based Basic EmONC training and is providing reproductive health supplies and kits to health facilities with support from UNFPA. With technical assistance from University Research Co.,LLC (URC), the quality improvement approach has started with the initial group of health facilities. The first training on quality improvement took place during January in

Chambucha, a remote community in North Kivu Province.

This was followed by site visits to select facilities.

Overcoming challenges

These achievements didn’t come without challenges. DRC is currently in the middle of the rainy season, making it very difficult to access some communities and provide assistance to beneficiaries and supervise activities in the various health areas. In some cases, the community members themselves assist in carrying supplies on their heads where the roads are impassable and cars cannot pass.

This is a critical period of continuous follow up and support to the quality improvement teams at each facility by the coaches, supported by the URC QI Advisor and International Medical Corps’ R2HC team, to continuously identify problems, test solutions and monitor outcomes.

I am very happy with the way this project is going and look forward to the next phase.

Joel N. Ambebila, DRC Programme Coordinator at International Medical Corps

Stay updated

Sign up for our newsletter to receive regular updates on resources, news, and insights like this. Don’t miss out on important information that can help you stay informed and engaged.

Explore Elrha

Learn more about our mission, the organisations we support, and the resources we provide to drive research and innovation in humanitarian response.