Addressing the needs of forcibly displaced populations during a pandemic: early learnings

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the urgent need for refugees and internally displaced people (IDPs) to have equitable access to public health care systems, wherever they are in the world.

This is one of the key messages to policy makers from academics currently researching health systems’ responses to the virus in Colombia, Gaza and Lebanon.

Speaking in an online discussion I chaired recently during the 6th Global Symposium on Health Systems Research, Dr Arturo Harker Roa, associate professor at the Universidad de los Andes, Dr Karin Diaconu, research fellow at the Institute for Global Health and Development at Queen Margaret University, and Dr Akihiro Seita, UNRWA’s Director of Health Programme, shared some of their preliminary findings and key messages for decision makers.

While the contexts, areas and even research approaches they discussed differed, their insights were strikingly similar.

Researching ways to help systems adapt to the pandemic

By the end of 2019, there were nearly 80 million people displaced from their homes worldwide. Increasingly, these refugees and IDPs are hosted by countries with few domestic resources, putting additional strain on already fragile and under-resourced health systems.

Anticipating the potentially devastating effects of the COVID-19 outbreak on the world’s displaced persons and their host communities, in March 2020 Elrha’s Research for Health in Humanitarian Crises (R2HC) programme launched a call for responsive research proposals.

As the funded studies begin to yield findings, their evidence is intended to help operational actors and policymakers tackle the challenge of adapting health systems and COVID-19 public health service delivery.

There are currently 15 R2HC-funded studies underway around the world, designed to generate rapid evidence to inform health systems actors in their response to COVID-19. These studies are particularly aimed at understanding and addressing the needs of refugees and the internally displaced people (IDPs). Among them, research projects in Colombia, Gaza and Lebanon, which were discussed in the panel.

The picture for Venezuelan migrants in Colombia

In Colombia — where around 1.3 million Venezuelans have fled to escape violence, insecurity and threats, and also suffer from a lack of food, medicine and essential services — the vulnerabilities of the current health system, particularly for migrants, have become more evident during the pandemic.

Dr Harker and his team are studying how the implementation and uptake of policies among Venezuelan migrants and Colombian citizens has impacted the COVID-19 response and health care access and use.

So far, their work suggests the current health system — which requires migrants to have a permit to access primary health care — is particularly inefficient during a crisis and needs to be re-examined.

There has been a significant drop in overall healthcare use in Colombia. Standardised hospitalisation rates for Colombians declined sharply, though they rose slightly for Venezuelan migrants nationally (5.5%). Overall, in 2020, at a national level, nearly twice as many Venezuelan migrants were hospitalised as demographically similar Colombians.

Other preliminary findings suggest a large variation across the 60 municipalities studied, in respect to the types of policies implemented, adherence to them, and healthcare use. Within those municipalities, there is also disparity — adherence to social distance measures differs between Colombians and Venezuelans, for example, as does their comparative knowledge of COVID-19.

These early findings require greater exploration. Which policies worked to prevent infection and death, for example? Did they work better in certain contexts or municipalities? What explains the overall drop in healthcare use? What has caused the variations in adherence by municipalities, and the differences between Colombians and Venezuelans?

Learning from experiences in Gaza and Lebanon

Meanwhile, in Gaza and Lebanon, UNRWA’s ability to learn from its past public health responses has enabled it to make informed and quick decisions.

Dr Diaconu is working with the UN agency to understand the effectiveness, equity, acceptability and scalability of strategies put in place by its health systems during the pandemic to sustain routine service delivery and mitigate the impacts of the virus.

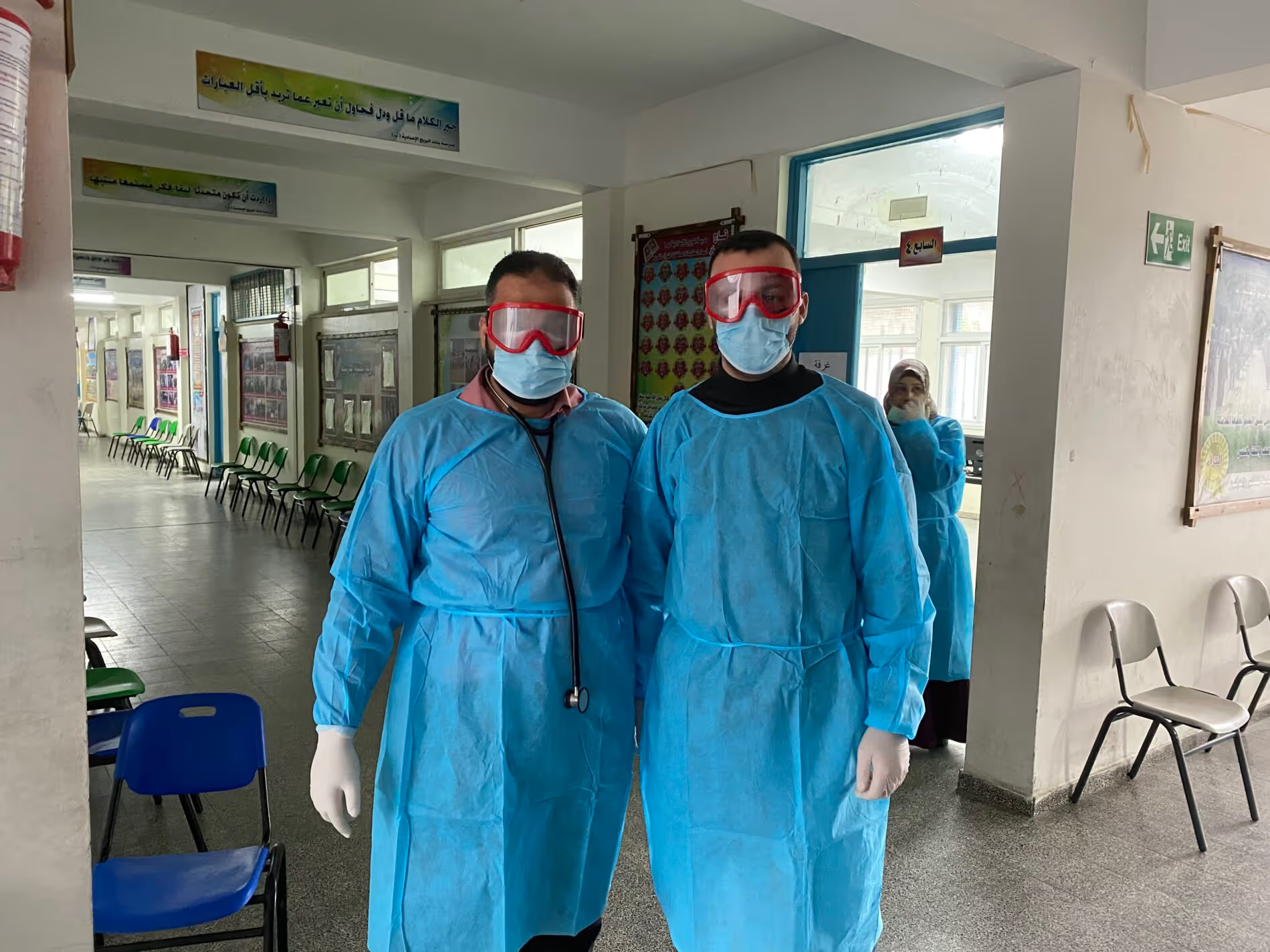

One of the early messages from this mapping exercise is to learn from what you know. Views from area and field levels, for example, have rapidly informed decisions — such as converting closed schools into medical points. This was done quickly in Gaza, helping implement a local community strategy and providing reassurance.

In addition, UNRWA’s willingness to learn and dedicate spaces to that learning has enabled resilient responses. For example, a team in Gaza convened to elaborate a food distribution system pilot, evaluate its impact and scale it up during changing circumstances.

There are also examples of absorptive strategies — such as staff working alternate hours, dividing labour and liaising with NGOs to deliver food and medication to COVID patients and families in quarantine. They have adapted — establishing toll-free lines and online consultations and support, creating isolation centres — and are seeking to transform the way things are done in the longer-term, including by considering how they can maintain a family health team approach in these challenging times.

What does this mean for health systems policymakers and their research partners?

What is clear from the discussion, and the early findings shared, is that COVID-19 makes vulnerable people more vulnerable.

The shocks and stressors which we are facing as a global community, and which are especially hard to manage for contexts with low resources and low social cohesion, will continue in varying forms.

The virus does not only affect refugees’ health, it affects their entire life. Our responses to it must be holistic to be effective.

A national health system response can only be effective when refugees and IDPs are included in it, and when all their essential needs are met — health, social and economic.

However, there is hope. We can transform our approaches to health systems in humanitarian settings. We can ensure there is no need for a parallel health system, because our national health systems are accessible to all those in need, regardless of their migration status.

For more information on these and other R2HC-funded COVID-19 studies currently underway, visit Elrha’s COVID-19 hub.

Stay updated

Sign up for our newsletter to receive regular updates on resources, news, and insights like this. Don’t miss out on important information that can help you stay informed and engaged.

Explore Elrha

Learn more about our mission, the organisations we support, and the resources we provide to drive research and innovation in humanitarian response.