Ndrelmba‚ perotiyapa and dora: Translating menstruation

In August 2018 WoMena Uganda, with our implementing partner Welthungerhilfe (WHH), visited Bidibidi Refugee Settlement in West Nile, Uganda, as part of our HIF-funded feasibility assessment of reusable menstrual products in humanitarian programming. In our preparatory efforts, our trip focused on recruiting and training research assistants and community facilitators. In carrying out this activity the WoMena Uganda team was reminded of the critical importance of language in menstrual health education and programming.

WoMena Uganda’s preparatory visit to Bidibidi prior to undertaking baseline research and implementation provided an insightful opportunity to test the translation of concepts and terms related to menstrual and sexual reproductive health (SRH). We were interested in testing the translation of these terms in both an educational/training context and for the purpose of our data collection tools.

Attention to language is of critical importance in this study given the diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds of the project participants. Bidibidi Refugee Settlement is home to many diverse languages, chief among them Juba Arabic, Acholi, Kakwa/Kuku and Lugbabra/Aringa. In keeping with Ugandan Refugee policy, 30% of our project activities target the local host population, further diversifying the project’s cultural and linguistic context.

Translation for education

Menstrual education is increasingly observed as a key factor in sustained behavioural change related to menstrual health, particularly those involving new innovations such as the menstrual cup and reusable pads. It is vital to ensure that key terms are translated appropriately and understood in local languages for safe and effective use and uptake. Our training of refugee and host population community facilitators provided an interesting opportunity for participatory learning and allowed us to test how concepts and terms might translate in community training sessions.

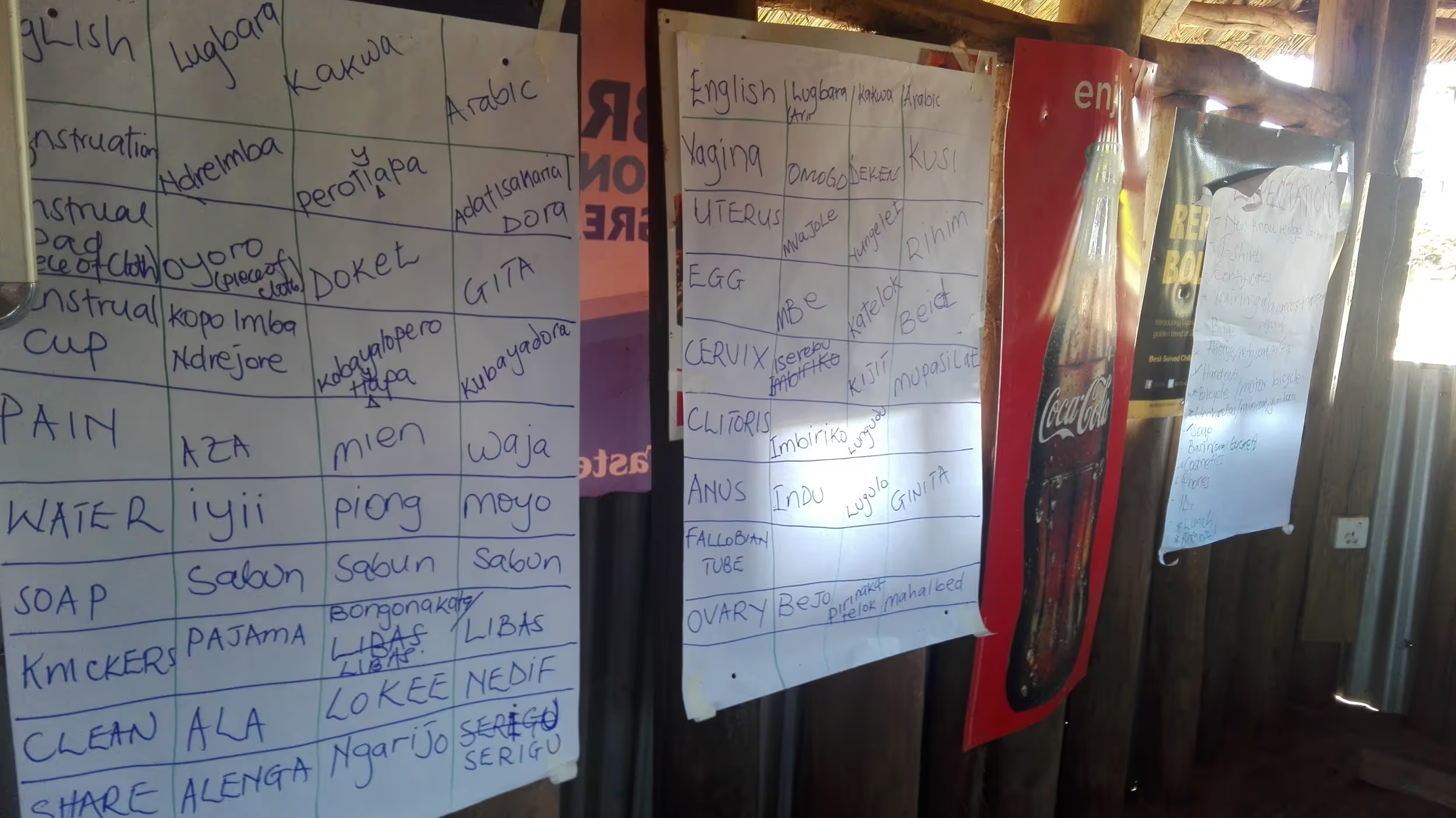

In each training session, WoMena Uganda’s trainers mapped the four languages into large grids on A3 paper to visualise these differences. Participants were encouraged to share local terms relating to the reproductive anatomy and menstruation, as pictured on the right. This was useful for understanding the colloquial terms for menstruation in local dialects, the diverse terminology relating to SRH anatomy, and the inappropriateness of certain translations in some cultural contexts. For example, the translation of ‘vagina’ into Kakwa or Kuku (two different variations of the Bari language group) which despite being the recognised term, was seen as too vulgar for conversational use. We were also not able to identify a translation for the concept of the hymen in some of the languages.

The diverse linguistic landscape of Bidibidi poses a logistical challenge. The diversity in languages required us to be flexible, utilising translators during training sessions, after assessing literacy levels and linguistic differences. We found that our standard internal training evaluation tools failed to capture participant learning due to their literacy basis. Mid-training, we adapted our approach and piloted a voting-based evaluation test approach, as pictured to the left.

In this exercise participants voted by placing crumbled pieces of paper into cups correlating to pictorial responses for questions that were read out, an approach we have used previously in our work in Karamoja in north-eastern Uganda. Whilst this approach does expose the evaluation process to increased bias, it was a useful lesson in the need to adapt our evaluation tools to the context within which we were working. This exercise also proved to be very entertaining, with our community facilitators laughing and rushing to cast their votes. The exercise also allowed us to give direct feedback on the correct responses, further strengthening learning.

Translation for research tools

We also recruited research assistants who have the necessary linguistic skills to best carry out our research and limit the extent to which it might be necessary to work through translators during research activities. Assessing linguistic differences prior to baseline and implementation is very useful in enabling us to adapt our research tools to the given context, ensuring that terminology utilised is appropriate. We conducted the same translation exercise with our research assistants, translating key terms, to ensure that our research assistants’ interpretation of the commonly used terms matched that of the communities within which we will be collecting data.

Understanding the linguistically diverse humanitarian context of Bidibidi is a crucial aspect of this feasibility study as it gives an indication of the challenges and solutions that are needed in order to feasibly scale these menstrual innovations.

Stay updated

Sign up for our newsletter to receive regular updates on resources, news, and insights like this. Don’t miss out on important information that can help you stay informed and engaged.

Related articles

Explore Elrha

Learn more about our mission, the organisations we support, and the resources we provide to drive research and innovation in humanitarian response.