Learning about understanding

How do you ensure everyone understands what services and support they are entitled to, if you don’t know what language they speak?

In north-eastern Nigeria, that is a problem facing humanitarian organizations trying to support the 1.7 million internally displaced people (IDPs) and others affected by the conflict and food crisis. Translators without Borders (TWB) has carried out research on the issue, developing our own methodology in the process.

Data is not routinely collected on the languages people speak and understand in north-eastern Nigeria. In a country with over 500 recorded languages – 28 of them in Borno State alone – it is hard to predict which will be the best means of communication with any group. Humanitarians have so far dealt with the problem for the most part by using a lingua franca – either Hausa, spoken by over 25 million people in the region, or Kanuri, with over 3 million speakers. Yet before now, nobody has known whether those communication efforts are effective across the affected population.

In July 2017, TWB set out to answer that question, building on our experience of comprehension testing in Kenya, Bangladesh, and Greece. In collaboration with NGOs Oxfam and Girl Effect, we tested actual comprehension levels in English, Hausa, and Kanuri among IDPs and host community members in Borno State. The tests used simply worded information materials developed by Oxfam’s protection team. Because literacy levels are generally low, the materials were shared in three formats: text-only, text with a picture, and audio. Respondents also answered questions on the language and format they preferred to receive information in, and on age, place of origin, and education level.

This was our biggest comprehension study so far: almost 1,000 people at five sites, from 15 places of origin and speaking 29 first languages. We learned a lot – both on how best to communicate with affected people in these locations, and on how we can further refine our comprehension testing.

What we learned about language comprehension at these sites

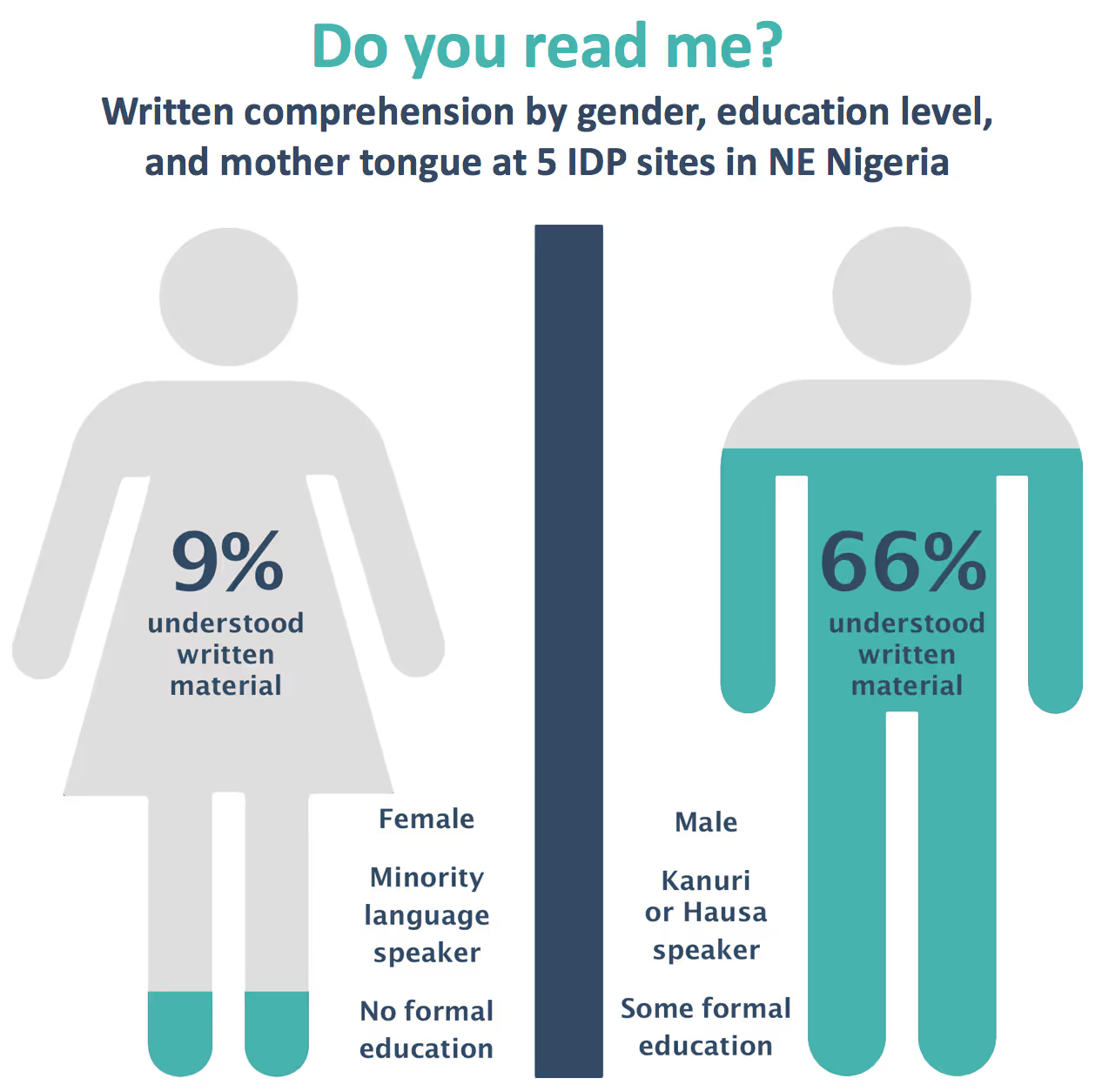

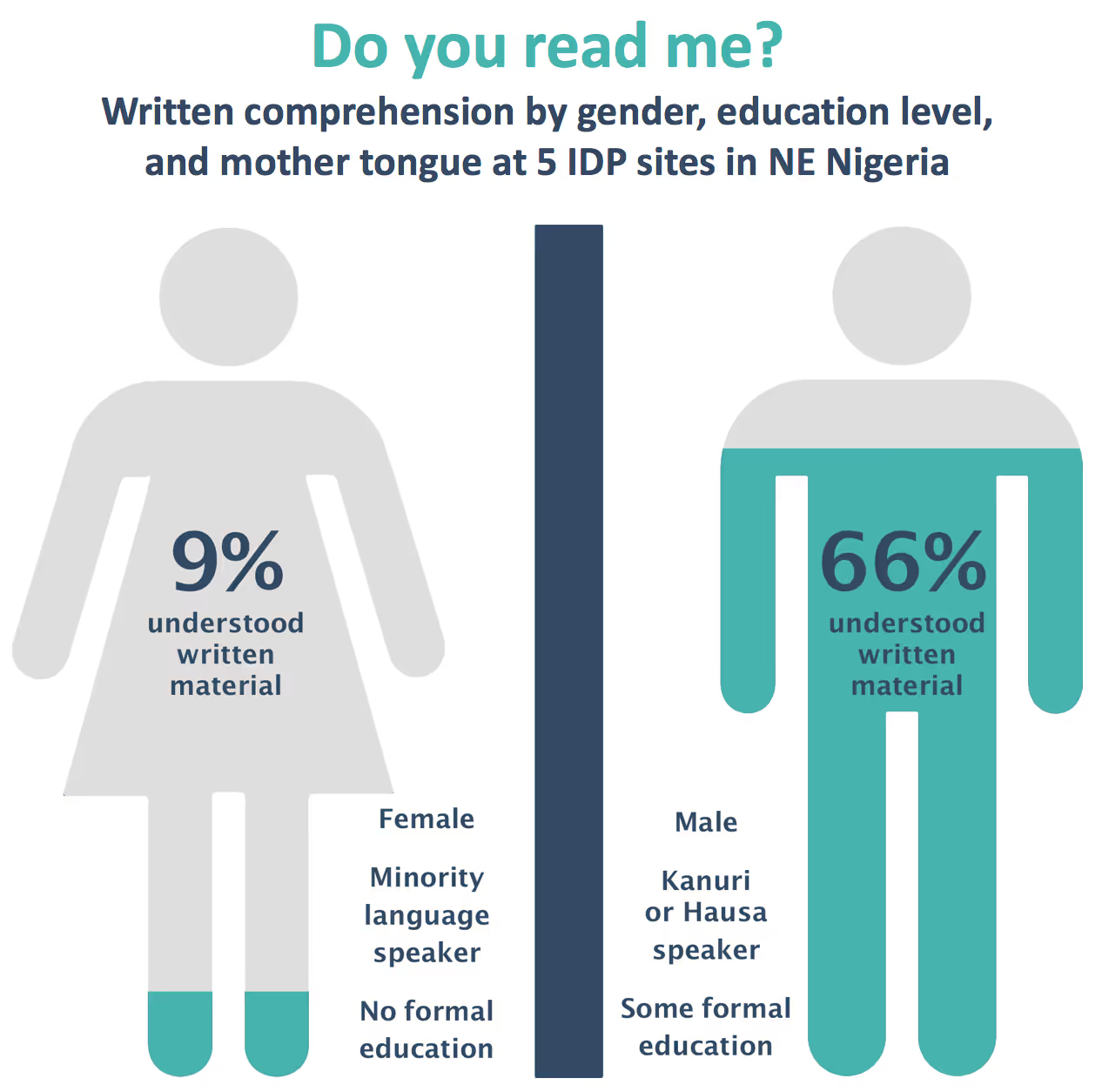

- Just 23% of those tested understood written Hausa or Kanuri – the languages used to communicate with IDPs at over 90 percent of sites.

- 79% percent of the sample preferred to receive information in their own language, with speakers of some minority languages showing a stronger preference than others.

- Information in audio format in Hausa and Kanuri was 97% effective across all groups.

- Less educated female minority language speakers scored lowest across all sites: effective communication with this group will need simplified content and mostly verbal mother tongue communication.

What we learned about the methodology

It proved hard to control for biases such as prior exposure to the materials, and the level of difficulty of the comprehension questions asked.

The information materials tested were already in circulation at IDP sites. That means the findings tell us a lot about how much people understand of the information they are actually receiving. But it also means respondents may answer a comprehension question correctly because they are familiar with the material, rather than because they understand the content when they see or hear it.

That will always be an issue when we test to fill an information void on which languages people understand. Using the methodology to test comprehension of new materials before dissemination would remove this bias.

Subjective differences in the clarity of the materials and the difficulties of the questions asked to test comprehension were the other area of bias it was hard to control for.

While comprehension of English was low in other formats, it was surprisingly high for English text accompanied by a picture. This may indicate that the picture chosen for the test in English was more self-explanatory than the one used for the other languages. However, it may also suggest that more work is needed on what makes a picture easy to understand in this context.

Scores may also say more about how hard the various comprehension questions were than about respondents’ actual understanding of information in a given language and format. Asking multiple questions for each item of content will make the survey longer to administer, but should help correct any bias on this point.

What next?

We are sharing the findings with humanitarian organizations in Nigeria and discussing how TWB can boost translation and interpreting capacity to fill the gaps identified, while expanding comprehension testing to other areas.

Meanwhile on the other side of the world… TWB will be taking learning from this process to comprehension testing in a very different and challenging context, with Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh. Watch this space!

Stay updated

Sign up for our newsletter to receive regular updates on resources, news, and insights like this. Don’t miss out on important information that can help you stay informed and engaged.

Related articles

Explore Elrha

Learn more about our mission, the organisations we support, and the resources we provide to drive research and innovation in humanitarian response.