How can cultural history of ‘health’ change disease perception & reduce stigma?

How can cultural history of ‘health’ change disease perception &; reduce stigma? A brief comparison of Influenza, 1918-1919, and Ebola, 2014-2015

Sonya de Laat, Postdoctoral Fellow in Humanitarian Health Ethics, McMaster University

The year 2018 marks one-hundred years since the outbreak of the great Spanish Influenza pandemic that struck in the wake of the First World War. While it may not be obvious—and certainly the two are not homogenous—there are similarities between that infamous flu outbreak and the Ebola outbreak that made global headlines and spread through multiple international borders in 2014-16. For instance, like the Influenza pandemic, Ebola was particularly virulent within populations of people otherwise deemed young and healthy. Normally viral fever diseases affect the very old, the very young or the immunosuppressed. The flu, killed some 50-100 million people worldwide, infecting some 500 million (CDC) through three successive waves between January 1918 and December 1920. Soldiers returning from the Great War were among the hardest hit. During the West African Ebola outbreak, some 11,000 people died across six countries, again, many who were young and in the prime of their lives.

This post presents a brief overview of historical similarities between the two viral diseases. It is not meant to conflate the two outbreaks or diminish either’s significance. On the contrary, this comparison is intended to open lines of questioning about the responses to diseases such as Ebola Virus Disease, particularly to diseases that are associated with dramatic symptoms and that have been scientifically and socially neglected.

Since 2016, the Humanitarian Health Ethics research group has been exploring experiences of palliative care during the 2014-15 Ebola outbreak in Guinea through their R2HC-funded project “Aid When There is ‘Nothing Left to Offer.’” In-depth interviews with healthcare providers, survivors, and psychosocial &; spiritual supporters provide first-hand accounts of the lived experience of the disease. Medical historians have noted there is a paucity of patient voices in histories of pandemics such as Spanish Influenza. Let’s not make that mistake with Ebola. Patients’ voices and stories are central to “any real understanding” of disease experiences (Bristow 2010). Applying a cultural history lens to a current health issue can offer new perspectives on both past and present responses, which is something that is often underappreciated for its importance in shaping the future.

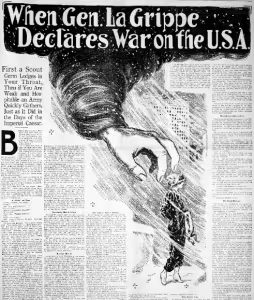

[caption id=attachment_15970" align="alignleft" width="254"]

Figure 1. The Ogden standard. (Ogden City, Utah), 29 Jan. 1916. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.[/caption]

On influenza symptoms, 1918-1919:

“Though for some these initial symptoms passed without complications in a week or so, for others the suffering grew worse. Delirium and unconsciousness often followed, and as the lungs filled, a blue or purple coloring overcame the extremities and the face. For some, too, bloody fluids drained from the nose, creating a grisly scene for families and caregivers. Death soon followed. Some patients died in a day, though most endured a longer illness—perhaps three or four days, a week, or 10 days of crisis.” (Bristow 2010)

Ebola virus disease symptom experience, 2014-15:

“Anemia, if you empty yourself of your blood… it comes out in his nose, …, wherever there are holes, there is bleeding. Where are you going to go, where are you going to stay? We cannot clog our ears so that it does not bleed, the a-, …, everything. The bleeding, Ebola, really, that is inexplicable. It is the anemia that carried a lot even [to their deaths].” Participant 07

On influenza despair, 1918-1919:

“I got to the point where I didn't care whether I died or not” (Clifford Adams quoted in Bristow 2010).

Ebola virus disease despair experience, 2014-15:

“… since entering, I saw only death. And all my thoughts were on death. Because when you come in, it's the smell of death and of people suffering. You see people screaming and lamenting in pain, they are seriously ill without help. Nobody comes to see them. That's what scared me. I told myself that I will have the same fate. Doctors only lead you without saying anything and doing. Then they go out. You will see some patients bleeding next to you. You will find that you really, really do not care about everything. Nobody comes to their rescue. That's why I thought to myself that I came here to die.” Participant 04

On influenza mortality, 1918-1919:

“In one family two children were found dead, and the father and mother and three other children so ill that they were unconscious of the fact.”

A report from the Red Cross in Baltimore acknowledged that such circumstances were not uncommon: “Conditions were found by the nurses in most cases visited to be of most serious nature, requiring immediate attention. Several cases reported revealed the fact that there were not only two and three sick patients in one bed at a time but a dead body as well.”

Ebola virus disease mortality experience, 2014-15:

“In the same corner, the child was negative, his mother was strongly positive, the mother refused to remove her child. A stubborn [woman]. When we arrived, we separate her from her child. She came and took her child, she gave him milk. The child sucked the milk and the child became infected. And the mother died while the child was nursing. When I saw the seriousness of the risk that the child encountered there, it made me cry.” Participant 06

[caption id="attachment_15971" align="alignleft" width="219"]

Figure 2. Influenza precautions, Seattle, Washington. American Red Cross, circa 1918-1919. LC-DIG-anrc-02654[/caption]

On influenza stigma, 1918-1919:

“even those children taken in by relatives sometimes suffered from the rejection of unfeeling families and a sense of being abandoned, unwanted, and helpless” (Bristow 2010).

Ebola virus disease stigma experience, 2014-15:

“[she] was intelligent, so that one day when she returned home, she said that since she took care of [name], she does not feel well any more. She said was bleeding. It scared everyone, and people immediately shouted at her. People did not let her talk anymore. In fact, the people who were there prevented her from speaking, from saying what she felt was wrong. People said she's lying. But in reality, she was right, because a few days later, she died too.” Participant 05

Other similarities:

Neither Influenza of Ebola Virus Disease had vaccines at the time of these historically significant outbreaks. At least Ebola was understood to be a virus, making anti-viral therapies a possibility.

Influenza on the other hand was not known to be a viral disease till the 1930s so medical professionals were relying on and trying all sorts of traditional and untested treatments—often without keeping proper records, let alone reporting. Despite Ebola being identified as a virus, vaccines and viral therapies were virtually non-existent and were only administered as part of research experiments on compassionate grounds.

During the Influenze outbreak, serums made from the blood of convalescent ‘flu patients was being applied. This tactic was also tested during the 2014-15 Ebola outbreak.

“TLC,” or tender-loving-care, was the ‘standard of care’ during the 1918-1919 influenza outbreak (Herring). During the 2014-15 Ebola Virus Disease outbreak symptom management and comfort care—or (unacknowledged) palliative care—were the available relied upon therapies. These interventions proved life-saving in an untold number of cases, but more often the most they could offer was hope and comfort. To combat a public health emergency with comfort and hope is certainly important and necessary, but it is woefully inadequate and insufficient in the face of exponential growth in confirmed cases and high mortality rates.

[caption id="attachment_15969" align="alignleft" width="300"]

Figure 3. Advertisement 1918.[/caption]

Voices of the past echoed in the present

Undoubtedly there are similarities that go beyond the experiences and descriptions included here, for instance the amplified impact of these diseases on poor or already marginalized populations. Being exposed to these similar voices give us pause to think also about the differences between these two historically significant public health emergencies as well. Global disparities, histories of discrimination, and myths of the exotic certainly plagued efforts of effective and efficient interventions a century ago. While critical reflections are still emerging on the recent West African outbreak, those dimensions that had a negative impact on the ‘flu a century ago are likely to be found amplified in the case of Ebola virus disease unless more narratives that normalize it or align it with diseases past circulate minus sensationalism and hysteria. Whether or not these quotes and voices make us reflect on compassion and reliance in the face of great struggle, or inspire disciplined training and reasoned preparation for the (inevitable) next public health emergency is up to the reader to decide.

References:

Bristow, Nancy K. (2010). "It's as bad as anything can be": Patients, identity, and the influenza pandemic. Public health reports (Washington, D.C. : 1974), 125 Suppl 3(Suppl 3), 134-44.

CDC: Centres for Disease Control. (2018). Flu 'made everybody afraid' https://www.cdc.gov/features/1918-flu-pandemic/index.html

http://www.nbcnews.com/id/16194254/ns/health-infectious_diseases/t/survivors-remember-global-flu-pandemic/#.W9C9hC_MzOQ

Herring, Anne. (2006). Anatomy of a Pandemic: The 1918 Influenza in Hamilton.

Stay updated

Sign up for our newsletter to receive regular updates on resources, news, and insights like this. Don’t miss out on important information that can help you stay informed and engaged.

Related articles

Explore Elrha

Learn more about our mission, the organisations we support, and the resources we provide to drive research and innovation in humanitarian response.